First Published: January 12, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.5541

In 1991, the federal government launched Healthy Start to improve maternal-child health outcomes. In 2021, the program provided more than $115 million in funding for 101 community collaborations to improve access to perinatal care, empower women to adopt healthy behaviors, and provide pregnancy and early childhood supports. Although infant mortality rates have improved, the nation’s maternal mortality rate increased from 17.4 deaths per 100 000 live births in 2018 to 23.8 deaths per 100 000 live births in 2020, with the rate for Black women nearly triple that of White women. The US has the highest maternal death rate among high-income countries—nearly 3-fold higher than France, the country with the second-highest maternal death rate.

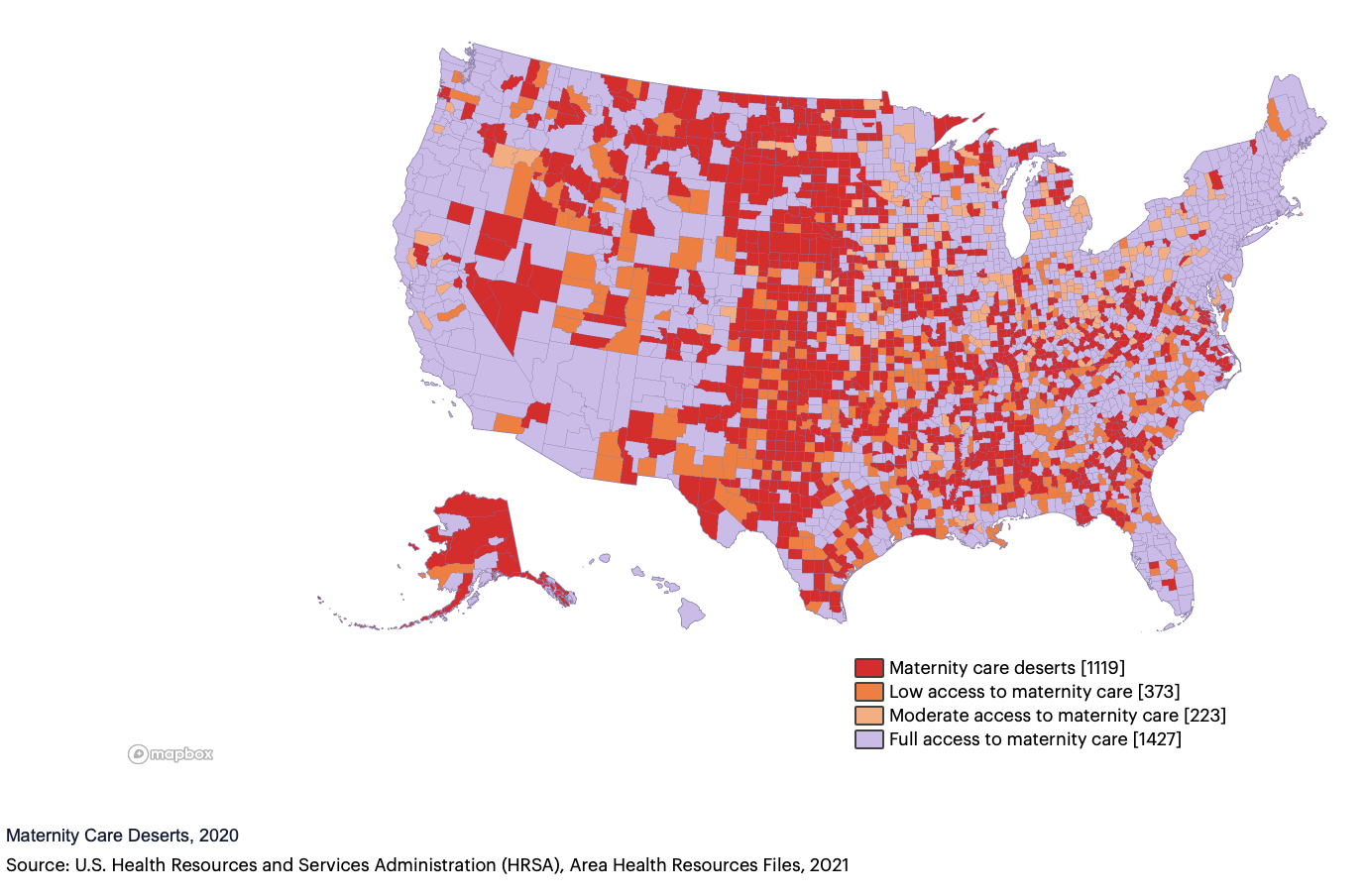

Within this context, childbearing services are becoming scarcer. Nationwide, more than 400 maternity services closed between 2006 and 2020. Between March and June 2022 alone, 11 health systems announced they were closing their obstetric services, citing low birth volumes and staffing challenges. As birthing units close, obstetricians and nurse-midwives are more likely to leave the area, exacerbating “maternity care deserts.”

Maternity services are especially scarce in rural areas. Between 2004 and 2014, 9% of rural counties lost hospital maternity services; another 45% had no maternity services to begin with. Rural areas have greater proportions of Medicaid recipients than urban areas, with Medicaid paying substantially less than private insurers for child birthing. Ongoing closures of rural health services impede hospitals’ abilities to improve maternal and infant outcomes.1

Two strategies could reduce maternity care deserts: expanding community-based models that are safe and affordable for low-risk women, and addressing workforce challenges.

Community Models of Perinatal Care

Child birthing centers (CBCs) have demonstrated excellent outcomes for women with low-risk pregnancies. Freestanding CBCs provide perinatal care, including labor and delivery services, using a midwifery and wellness approach, but partner with hospitals to provide care if complications arise. A hallmark of CBCs, the provision of continuous support during labor is associated with shorter labor, fewer cesarean deliveries and vaginal interventions, newborns with a high Apgar score, and higher patient satisfaction.2

Similarly, continuous support is characteristic of home births attended by a certified nurse midwife (CNM) or certified midwife (CM) (the term certified midwife refers to all licensed midwives who are not nurses; they are educated to provide perinatal care, including in women’s homes and childbearing centers). Home births with CNMs or CMs who are part of an integrated network of care have comparable or better outcomes compared with in-hospital births for low-risk women.3

In 2016, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists affirmed women’s rights to childbearing choices, including CBCs and home births, when eligible. Both models cost considerably less than hospital birthing. One analysis estimated that a 10% increase in the use of these models would save more than $10 billion annually.

Workforce Challenges

The US has fewer health care professionals who offer maternity care, including obstetricians, than other high-income countries (except Canada). The number of midwives is 4 per 1000 births vs 25 to 68 midwives per 1000 births in comparable nations.

The safety and quality of care provided to low-risk women by CNMs and CMs in hospitals, CBCs, or homes is well established. One review found that midwifery-led “continuity models of care” were associated with fewer interventions (epidurals, episiotomies, instrumental births), higher patient satisfaction, and comparable or lower rates of maternal or infant adverse outcomes than other care models.4 Twenty-three states still do not permit full practice authority to CNMs.

Historically, lay midwives provided care to poor women in the US, particularly in the South, before there was a movement by physicians and nurses to restrict the practice of Black lay midwives.5 Much of the nursing profession opposed the use of licensed midwives who are not nurses until the 1990s. In 2022, the American College of Nurse-Midwives affirmed its support for CMs who are educated at the master’s level. As of 2021, 36 states license midwives who are not nurses, but only 18 of these states pay for their services under Medicaid.

The use of doulas is expanding as a cost-effective way of reducing health disparities by providing support to women before, during, and after labor and delivery, including through community-based organizations.6 Doula support is associated with fewer cesarean and interventional vaginal births, as well as lower rates of postpartum depression and anxiety. This movement is growing, including through Healthy Start funding of community-based doula initiatives.

Policies to Reduce Maternity Deserts

In June 2022, the White House published a blueprint for addressing maternal health disparities, including improving the readiness of hospitals lacking maternity services to provide safe deliveries.7 Wider availability of evidence-based midwifery-led care and doulas for low-risk women can prevent and rectify maternity care deserts. The following key policy changes could accelerate this movement:

Paying CNMs, CMs, and doulas for perinatal care in all settings. This includes federal recognition of CMs and payments under Medicare and Medicaid. TriCare (which does not pay for care by CMs) and private payers should cover these services, and states should amend their Medicaid plans to do likewise.

Adequate coverage by all payers for eligible births at home and in freestanding CBCs. Periodic evaluation of Medicaid payments, which cover about 40% of all US births, is needed to ensure they cover reasonable costs.

Invest in growing and diversifying the perinatal workforce. The federal government currently funds states for innovations related to perinatal home visitation, including clinical care and workforce development. These supports should be enhanced, especially for programs targeting Health Professional Shortage Areas, including scholarships, loan forgiveness, and graduate medical education funding for institutions that develop obstetrical residency programs serving rural hospitals.

Invest in building community-based maternity services. To end maternity care deserts, start-up funds are needed for planning, launching, or expanding services. An approach comparable with the Hill-Burton Act of 1946, which invested in increasing the nation’s capacity for acute care hospitals, is needed to expand community-based maternity care that includes primary care when limited.

The childbearing period is crucial to healthy children, mothers, and communities, but the US fails to ensure adequate perinatal and birthing care. Evidence-based, community solutions to eliminate maternity care deserts are within reach.

Article Information

Published: January 12, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.5541

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License. © 2023 Sonenberg A et al. JAMA Health Forum.

Corresponding Author: Diana J. Mason, PhD, RN, Center for Health Policy and Media Engagement, George Washington University School of Nursing, 1919 Pennsylvania Ave NW, Ste 500, Washington, DC 20006 (djmasonrn@gmail.com).

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

References

1.American Hospital Association. Rural hospital closures threaten access: solutions to preserve care in local communities. Accessed December 3, 2022. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2022/09/rural-hospital-closures-threaten-access-report.pdf

2.Hodnett ED, Gates S, Hofmeyr GJ, Sakala C. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD003766. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003766.pub5PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

3.Hutton EK, Reitsma A, Simioni J, Brunton G, Kaufman K. Perinatal or neonatal mortality among women who intend at the onset of labour to give birth at home compared to women of low obstetrical risk who intend to give birth in hospital: a systematic review and meta-analyses. EClinicalMedicine. 2019;14:59-70. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.07.005PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

4.Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, Shennan A, Devane D. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4(4):CD004667. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004667.pub5PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

5. Dawley K. The campaign to eliminate the midwife. Am J Nurs. 2000;100(10):50-56.PubMedGoogle Scholar

6.Van Eijk MS, Guenther GA, Kett PM, Jopson AD, Frogner BK, Skillman SM. Addressing systemic racism in birth doula services to reduce health inequities in the United States. Health Equity. 2022;6(1):98-105. doi:10.1089/heq.2021.0033PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

7.White House. White House blueprint for addressing the maternal health crisis. Accessed December 3, 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Maternal-Health-Blueprint.pdf